movie

Thank you to all attendees of Vertigo’s first online master class

We were almost 200 participants (at peak) from a dance lovers community from around the world

Welcome to share your feelings with us

The session will soon be available to those who missed or the timing did not fit

See you next Friday 8/5 at 11am Israel tim

Noa Rina and Meirav – Vertigo

Any donation is greatly appreciated

. https://secure.cardcom.solutions/e/xOlx

Vertigo Dance Company has the pleasure to invite you our dear golden age friends and dance lovers to move along with us during these intimidating days.

You all will be enjoying the distinct Vertigo’s dance language and movement, directed by Noa Wertheim – Artistic Director – VDC

which reflects on the ongoing awareness of Vertigo to Art, Human &Nature

The guided activity is filmed at the Vertigo Eco-Art village, Vertigo’s home, located in the midst of the pictures beautiful Ella Valley, located between Tel Aviv & Jerusalem, Israel

YAMA a full length piece by Noa Wertheim 2016

In Yama Noa Wertheim explores the human ecological footprint, dependency and the capacity to regenerate.

Noa observes the source of each movement and its effect on the environment.

RESHIMO

A full length work by Noa Wertheim 2014

Now that the world is slowly starting to open up again, it is a time to be very attentive. We have changed in many ways during these Corona times – a period of inward movement. Now the challenges we all are confronting, will be how we are able to integrate the deep insights we have gained from this difficult situation and bring them into our lives as things return.

Reshimo is about the imprint of a past impression left within. A Kabbalistic idea pertaining to the impression of light – the fine outline which remains when the lights are gone and are no longer there. Exploring the remanence of a vacant space this is a journey of the receptive soul as Reshimo lights the way to a future state.

In this new piece choreographer Noa Wertheim explores the passages between abstract and chaotic endless motion and the defined moment. Tracing the hidden primal existence to evoke passion towards everything that is contained within time and space including intervals and suspension. Incorporating rhythmic animation and playfulness the creative process provides for a new reflection of being present in the moment while observing the inner turmoil and accumulated burdens. Thus creating a pattern free space, a magnetic realm hosting the search for emotions, knowledge and creation.

https://youtu.be/-fEhfXpEvi4

An Amazing Panel with Noa Wertheim

“The Spring of Hope”

:Dive into it at this link

Shape On Us

Vertigo Power of Balance | Integrated Dance Center

“One. One and One” by Noa Wertheim will be posted on the weekly video series that features never seen before multi-camera edits of premieres by artists from around the globe, with a special introduction from Founder and Artistic Director Mikhail Baryshnikov.

May 7 – 12

Vertigo Dance Company

One. One & One (U.S. Premiere)

Jerome Robbins Theater

Filmed Mar 6, 2019

View Performance Program

https://bacnyc.org/performances/performance/playbac

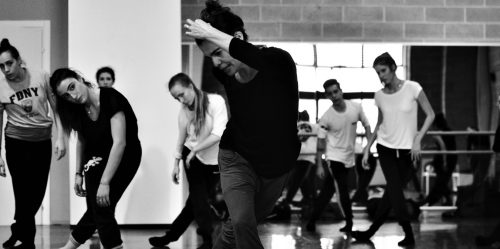

Vertigo Masterclass Sessions for Dancers and Movers

These days, more than ever, we have a desire to share the Vertigo dance language – that is based on movements from the inside out

We invite you to a unique enrichment day –

That will start with a lesson from Choreographer Noa Wertheim,

and continue with a Release and Research class from Rina Wertheim-Koren.

We will close the session with Merav Goldenberg in a guided meditation session.

for more info go to this link:

https://www.facebook.com/47217415839/posts/10157050258820840/

RAM KATZIR. (photo credit: YOAV DAGAN)

RAM KATZIR. (photo credit: YOAV DAGAN)

“Leela,” the new production from Vertigo Dance Company. (photo credit: RAM KATZIR)

Every choreographer will admit that each artistic creation bears its own impossible moments. The act of making art is intrinsically based on approaching the unknown, and most artists find themselves humbled by the myriad questions that a process can offer up.

On the afternoon that we spoke, Noa Wertheim was in such a moment. Just a few weeks away from the premiere of Vertigo Dance Company’s premiere of “Leela,” Wertheim was finding it hard to see the light at the end of her creative tunnel. There were glimmers but also a fair share of worries.

“It’s been a very difficult process,” she divulged. “I’m in the very hard moments right now. I’m on the edge of losing my mind.”

Wertheim is an old hand at exactly the type of insanity that was troubling her. After countless creations, running a leading Israeli troupe and establishing an ecological dance village, Wertheim knows how to take the good with the bad. She won’t sugarcoat her experiences, but she’s not too thrown by them either.

“We had our first few runs of the piece last week. I started to feel the heartbeat of the piece, and I started to smile again,” she laughed.

“Leela” is the newest to join the repertoire of Vertigo Dance Company, a list that includes “Birth of the Phoenix,” “White Noise,” “Mana” and many other works.

In Sanskrit, “Leela” means “a cosmic game.” It is the play between reality and God’s will.

“We started the creation a year ago, working on and off when there was time,” Wertheim said. “For the past two months, we’ve been a laboratory mode in the studio. Now we are at the end of it. I wanted some lightness. I felt that if I really looked at all the heaviness of the world around me, I would jump off of a peak. So I asked myself, ‘How do I treat this world with lightness? How do I play?’”

Wertheim brought this concept of play to her dancers and collaborators, as well as the idea of the space between Heaven and the real world.

“Ram Katzir, who is an incredible Israeli artist, designed the space. He created this huge set. It plays a huge part in the work. The stage has several layers, which goes along with the idea of the bigger picture,” she said.

A unique opportunity for a hands on experience of the Vertigo distinct movement language. Dancers from around the world are invited to participate in this challenging and inspiring 5-day workshop introducing the building blocks of the Vertigo dance language and Vertigo Dance repertoire. A rare opportunity to learn from dance masters and co-creators, choreographer and artistic director Noa Wertheim and her sister, assistant choreographer Rina Wertheim-Koren.

press here for more information and registration

Watching nine members of Israel’s Jerusalem-based Vertigo Dance Company perform One. One & One at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, you don’t think of green pastures and rippling brooks, you imagine rocky or sandy terrain being dug into and turned over and wrestled into fertility. Soil itself figures in this dance by Noa Wertheim, with Rina Wertheim-Koren as a co-creator. To sounds of rumbling, of thunder, of shovels at work, one man (Daniel Costa) backs across the front of the stage, carefully spilling a line of red-brown earth from a large bucket. Eventually, two additional lines of dirt will be laid down; later still, people rush around the stage, hurling more dirt from pails as they go.

When the members of this community dance, their feet trace circles and arcs and tangles in the increasingly mottled surface of their terrain. Since the choreography pushes them from jumping and striding into falling to the floor and rising again, their shirts and pants (by Sasson Kedem), their hair, and their faces become pocked with earth. This deters them not a whit. The soil even becomes part of a conversation: at some point, as Korina Fraiman and Costa approach each other slowly, one, then the other, throws a small handful of dirt at—yet somehow not at—his/her opposite; they end in a hug.

A remarkable solo by Shani Licht at the beginning of One. One & One alerts us to how these people move and think. She dances slowly and forcefully, as if she’s shaping her world, or perhaps being shaped by it. She arches back so far that you imagine her being pressed down. Her feet are often planted wide apart, her knees bent, yet her legs may twist around each other or kick out, her hips swing (but not enticingly). This is dance as work, but also as dreaming (some of her movements will reappear later, performed by others in other contexts). When three men lift her, set her down, lift her, and set her down elsewhere, they don’t look like furniture movers, but as if they’re trying to understand her. As she advances carefully, they follow her closely, ducking under and passing over one another as together they braid her long hair.

Roy Vatury’s set design abets the image of community. A long bench stretches along either side of the stage, and people often sit on these to watch what their colleagues are doing. The lighting by Dani Fishof – Magenta occasionally alters their world (say by projecting a checkerboard of squares on the floor), but the score composed by Avi Belleli enhances Wertheim’s choreography in quite particular ways—creating noises of chaos, gentling down, turning sweet, calling out, muttering, whistling, falling silent. At times, it provides a lively beat to manage the dancers into unison.

We come to know the choreography’s codes, if not always certain what they conceal. Whether moving in unison or individually, we see the dancers shake their hands vigorously, caress their heads, frantically gather in invisible substances, throw their arms high, slap and brush their thighs as if to rid themselves of dirt. But we’re not invited to consider anything as pantomimic. All these gestures, rhythmic and exact, are combined with forceful footwork, canted leaps, spins, big spraddle-legged jumps, and falls to the floor. At moments, you can see a hint of a folk dance, re-imagined.

There are mysteries. Licht and Hagar Schachal, standing close together and facing each other, might be fighting, but they’re not. They circle one another, lock together, almost butt chests, draw back, and lean in. Yet their duet looks non-combative, almost experimental, almost pensive. In a later sequence, Schachal has been dancing, bending into that back arch, watched by five others (Jeremy Alberge, Yotam Baruch, Sándor Petrovics, Etai Peri, and, as I remember, Liel Fibak). When they begin rushing around, you sense that they are following her, wanting to help her; she doesn’t seem to feel chased. However, when they catch her and lift her lying flat and prone, you become uncertain. They run with her this way, put her down, pick her up again, travel elsewhere. Finally, all five pin her down by lying over her; she tries unsuccessfully to get away, but they roll her to a corner and, finally, out of sight.

When Fibak dances close to the audience in the Baryshnikov’s black-box Jerome Robbins Theater, you notice that her gray shirt gets pulled up by her motions, and that she’s unconcerned about that. Some of the solos that erupt like hers make the dancers appear to be buffeted by strong winds or toppled by unseen forces. Yet they weather all these storms, the women as strong as the men. Continuing a sequence in which the women charge erratically across the stage, each launching herself onto one of the waiting men, Korina Fraiman not only jumps onto Petrovics many times, she ends up with him draped over her shoulder and carries him offstage. She is the smallest of the women; he is the tallest of the men.

The movement may be fierce but the dancers’ concern for one another is constant. Those who come and go on the benches seem always ready to join or intervene. At the end of the piece, when Licht and (as I recall) Petrovics are clinging together and leaning apart, and a cello is singing sweetly, the others stand in place, their arms spreading like wings—would-be angels flying nowhere. Finally, as the music dwindles into sustained tones and a high held note, one man just sits quietly, watching an empty stage as the lights dim.

This powerful piece of Wertheim’s conveys a desire for unity in a dangerously fragmenting world, whether that “world” is an exterior landscape or an interior one. Or both.

“One. One & One”

Vertigo Dance Company

Baryshnikov Arts Center, New York

March 6, 2019

by Tom Phillips

copyright 2019 by Tom Phillips

Except for a neat row of dirt at the front of the stage, the opening section of “One. One & One” by Israel’s Vertigo Dance Company looks much like the closing elegy of George Balanchine’s “Serenade.” It’s a solemn communal idyll, to sonorous cellos in a minor key, with a motif of dancers leaning on each other for balance and support. They seem to be a close-knit group, working out complex tasks together –- as when three men braid the hair of a woman while she uses her long tresses to pull them across the stage.

Photo by Stephanie Berger.

The communal spirit stays as more dirt is spread in the rectangular, closed space. But the mood changes suddenly with the sound of a cannonade — big guns, firing in the distance. After that, the dirt and the dancers start to fly, and the communal idyll is transformed into what looks like an army boot camp, whipping troops into combat readiness. The motif here is “bring it on,” with dancers lining up on each side of the stage and charging at their opposite numbers, trying to breach their defenses. Every charge is repelled!So much for “Serenade.” This looks more like Socialist Realism, the kind of state-sponsored art that Balanchine came to America to get away from. And if it reminds you of the modern history of Israel, as seen by the State of Israel, that’s just what it looked like to me.

Vertigo Dance Company is sponsored by The State of Israel. That’s not to say all is victory and light in “One. One & One.” The only drama comes late in the piece, when a woman seems to freak out over the demands of this regimen. She breaks for the non-existent exits, writhes and struggles, but is stopped and subdued at every turn by multiple mates, finally hauled off by the scruff of her shirt and guarded by a posse until she calms down. She’s back in formation for the closing elegy, with cellos deepening, still in that minor key.

The dancers deserve credit for grace, intensity and endurance, and choreographer Noa Wertheim’s combinations are inventive as well as athletic. But the world created by this dance is claustrophobic and completely one-sided. Danger and conflict are all around, but they never enter the space. Disembodied foes shoot guns in the distance; the response is to close ranks and work the troops into a frenzy. The dirt seems an obvious reference to the land of Israel, the object of turf wars since biblical times. The title evokes the presence of two nations on that holy ground, but the work shows only one. And what we see isn’t war, just endless readiness, mounting stress.

If that’s what it’s like in Israel today, I’d freak out too.